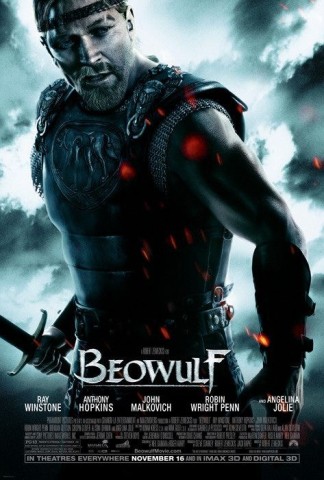

This marks Zemeckis’ second trip to that beautiful green screened wonderland, where he is able to realize the infamous dream of Orson Welles and his cinematic toy train set, a play area where a filmmaker could make any decision his mind could possibly dream up, albeit at the detriment of making the whole film in a CGI tank. While this can appear uncanny or disarming for some viewers, it benefits from the view that sometimes when a filmmaker wants to realize something so fantastic yet commercially unviable, no studio will step up to bankroll it. So Zemeckis found an alternative route bordering on the experimental, where he could make his very unusual take on the classic poem BEOWULF, while doing away with many of its cooked-in themes of heroism and evil, and instead focusing on the cyclical nature of illusory power being held by rulers risking their kingdom’s future because they cannot keep their dick in their pants. Featuring a version of Grendel so repulsive and sad, this rendition makes our title character less of a triumphant character, and more of an ignorant doofus with a penchant for inexplicably fighting naked, as well as crafting tall tales of the sea to enhance his image and bed bosomy maidens. If this movie is anything, it stands opposite the slate of macho-leaden blockbusters being crapped out at the time by Hollywood, such as TROY, KINGDOM OF HEAVEN, ALEXANDER, KING ARTHUR, and 300, movies so opposite the agenda of BEOWULF, that Zemeckis’ bizarre satire was quietly shuffled away into the pile of forgotten 2000’s studio epics. One thing is certain though, as the movie rises above the sword-and-sandal, heavy beard oil sub-genre it was relegated to: BEOWULF is proudly and defiantly the anti-300 movie we all forgot we needed.

Recommended Films