by Steven Prokopy

At a time when his stand-up career seemed to be on the rocks, comedian Marc Maron started taking smaller roles in films like Cameron Crowe’s ALMOST FAMOUS and Mike Birbiglia’s SLEEPWALK WITH ME. He also did something that may have seemed insane to some: he launched an interview-format podcast known as “WTF” that has now been on the air more than 10 years and aired more than 1000 episodes. After his career began to flourish, he starred in the critically acclaimed IFC show “Maron,” playing a version of himself, and not long after he ended the run of that series, he began accepting larger film and television roles, in such works as HBO’s “Girls,” MIKE AND DAVE NEED WEDDING DATES, Netflix’s “GLOW” and “Easy,” as well as in the upcoming DC movie JOKER, starring opposite Joaquin Phoenix and Robert De Niro.

But it’s his role as the cantankerous pawn shop owner Mel in director/co-writer Lynn Shelton’s SWORD OF TRUST that gives Maron his first truly starring role in a film. Working in a largely improvisational style with co-stars Michaela Watkins, Jillian Bell and Jon Bass, Maron has crafted a very funny and slightly political tale of a lesbian couple who inherit a Civil War-era sword with documentation claiming it somehow proves that the South won the war between the states. It’s a ridiculous concept and a very funny movie, as the four leads go on a journey to find a buyer willing to pay a small fortune for the sword. But it also taps into both the idea of the fluid nature of truth today and the dominance of conspiracy theories that seems to have been allowed to run rampant in America presently.

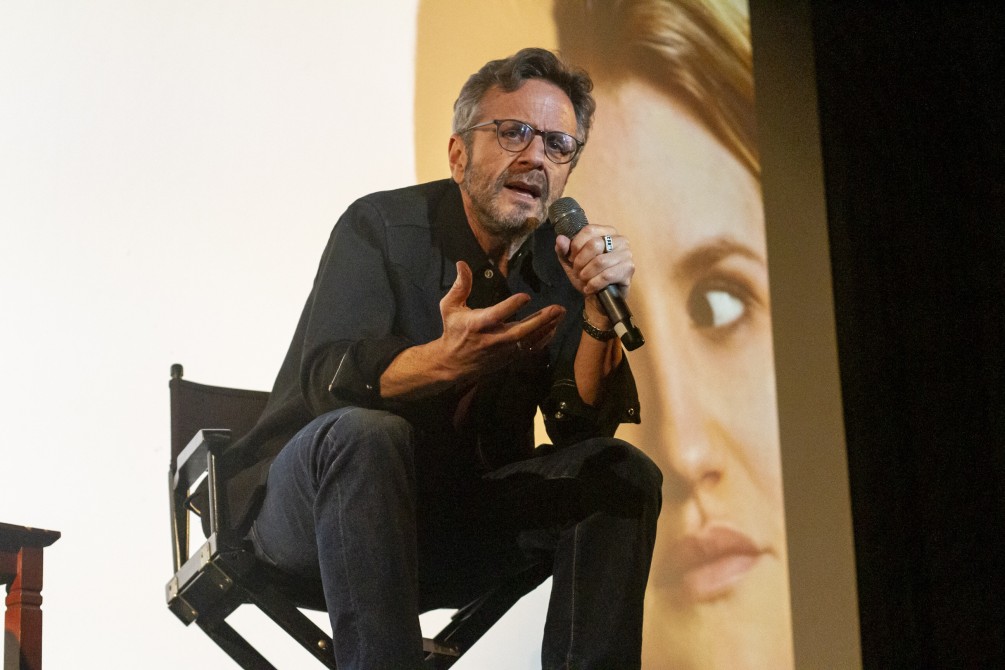

Maron and Shelton have worked together several times over the years; she directed episodes of “Maron,” “GLOW,” and his most recent Netflix comedy special, MARC MARON: TOO REAL. She and Maron had been working on a screenplay over he last few years, which was coming together slowly, and finally he challenged her to write something for him, which is what she and co-writer Mike O’Brien did. We spoke to Maron when he was in Chicago recently for two advance Q&A screenings of SWORD OF TRUTH, which is currently playing at the Music Box Theatre.

*********************

Question: You and Lynn Shelton have worked on several project together over the years. How did she first come to your attention?

Marc Maron: Lynn I got curious about a few years ago. Around 2015, I watched a movie of hers—I had seen HUMPDAY, but I think the movie I saw then was YOUR SISTER’S SISTER—and I had her on the podcast, and I was like “Wow, she’s the real thing, she’s great,” and we got along and had a lot in common, and then I asked her direct a couple episodes of the final season of “Maron,” which she did. I was not easy because I was learning how to do it and not that confident as an actor and knew I had a learning curve on that. And by the time she came in, that fourth season, it was the heaviest lifting acting wise because I relapsed on drugs, and that didn’t really happen, but I wanted to explore that, and she directed me. She was very intuitive about me and she’s a great laugher; she has a great sense of comedy and how things fit together. And she would give me direction on “Maron,” and I would immediately take it as a personal attack. She’d make suggestions, and I’d be like “Why would I do that?” But she learned how to manage a personality like mine, where a director will say “Why don’t we try it my way for one take, but we don’t have to use it.” I know that trick now. But over time, I learned to trust her. Coincidentally, we both did “GLOW,” and she directed a pretty heavy one for me—the last episode of Season 1. And then I asked her to direct my last comedy special. But I love her now.

Has your relationship to acting changed in the time you’ve known her?

MM: I’ve always wanted to act. When I started my podcast, I’d pretty much given up on anything I wanted to do actually happening, and I was okay with that. It was a Hail Mary pass, a real act of desperation. But in order to be okay with myself at that time, I really had to be like “Shit didn’t work out.” I did a little acting in high school and college and took classes here and there, but I never really focused on it and said “This is my life.” And it still isn’t, even less so now. But I knew when I started to do “Maron,” there was a learning curve because a lot of comics have shows, and they stink the first season, and I knew I would probably take that hit. I didn’t know how to be on a set, so all I’m thinking in a lot of scenes is “Should I move me hands? What do people do with their face when they’re talking?” And it takes time to get comfortable.

Also, I started having more actors on my podcast, so I could have free acting lessons, but I’m also interested in it. So over time, I got more comfortable. After doing comedy for 30 years, you realize that whatever you’re doing, you aren’t going to be good at it at first, and then eventually you learn to deal with stakes. If anything has happened over time, I’ve always been able to be present and I was relatively compelling, even if I was horrible. It’s just a matter of, when I watch myself in SWORD OF TRUST or a few other things, there’s a groove. When you get a skill set in place, you own that space for yourself. When young comics ask me “What do I do?” I always say “Do whatever the fuck you want. There’s nothing hanging over you. No one is expecting you to make money to perform yet, so don’t miss the opportunity to fail and do crazy shit, so you can determine exactly what your property is up there.” If anything has changed, it’s my ability to have emotions other than defensiveness and anger, and that’s in life and whatever I do creatively.

That’s why I talk to actors about craft, because it seems like there are a lot of different approaches. Weirdly, some of the things that help me out are like, if you’re shooting a TV show, you’re shooting in pieces and the pieces can be a minute long, and that takes three hours. There are a lot of things I still don’t know. I don’t know when it’s my coverage; am I even on camera? I’m giving it my all, but I’m not even on camera. But that’s okay, because I always want to show up for the other actors. I’m trying to enjoy it. I’m trying to learn to appreciate those moments when you’re in it. I’m happy my life doesn’t depend on the next acting job.

The best scene in the film is the one where the four of you are in the back of the truck just talking about your lives. It doesn’t forward the plot at all, but we learn so much about all four of you, and that was mostly made up in the moment, right?

MM: Well this is the land of improvisers, and I get this gig that is mostly improvising. But I don’t do that kind of improv, so I was intimidated at first because I’m not a Second City, sketch comedy guy. But I’m around all of these top-notch improvisers, and all of my stand-up is generated in real time on the stage; that’s how I write. So I’m comfortable improvising, but there was a certain level of insecurity. And after the first day, I’ve got people going way over the top and everyone is doing these never-ending riffs, and I said to Lynn, “If you don’t fucking ground these people into real characters, I’m just going to be the doofus straight guy for the entire fucking movie.” And she kept saying “This is your movie; you’re the lead,” and I’m like “I’m not seeing it!” But I do like that process and I can access emotions. People talk about that scene a lot, and Lynn and I did put some backstory in place. The only thing it said in Lynn’s scriptment was “They get to know each other in the van.”

The weird thing about acting is, I used to get envious of other actors, and I’d always ask them “Do you really become the other guy? Like you don’t even know who you are anymore?” That’s can’t be true. And then I start to realize that I’ve lied to people in my life, to their faces, and they believed me. If you’re a liar in any capacity and you get away with it—if you’re an actor, make note of that skill, because in order to do that, you have to put some serious backstory into place so it’s convincing.

But in that scene, I had some of my own personal backstory but then I had my experience living on the Lower East Side in New York, and I was never into those kind of drugs—I’m not a dope guy—but I used to live on 2nd between A and B in the late 80s, and there was a dope doorway right next to where I live, and the same people would come every day to score dope, and I would see them, and that was the first time I tried getting clean from what I was doing. So I started to implant memories of the people there, and then I started to remember it as if I was one of them, and I kind of believed it. Mel is different than me in that he’s committed and resigned to heartbreak, and that’s how that happened.

Also, it was a fucking horrible day. We were shooting outdoors in Alabama in the middle of the summer, and this was supposed to be the one day we were in a studio, and we were like “It’s going to be nice and air conditioned”—didn’t work! So we’re in the back of that truck for nine hours in a hot studio, and I’m at the end of my rope, dude. I’m about to snap, and I think the version she used was the last take on that scene, and I was livid and hot and upset, to the point where, after we wrapped that day, I couldn’t even hang out to be congratulatory. I was about to ruin the day for everybody.

How much backstory do you want to know before you agree to do a movie these days?

MM: The backstory is going to the idea of the writer—on some level, that’s helpful; on another, how much do you really use? But some actors use a lot of backstory, and maybe there will be a time when I use a lot. The fact that this guy had some of my backstory and other stuff that wasn’t quite like me. We were shooting in a real pawn shop, and I didn’t know how to sell stuff or how pawn shop stuff worked, but the guy who owned it told me a couple things and I integrated it pretty quickly. I was able to look like I owned the space. But backstory is somewhat helpful, but if it’s too complicated, it’s like “I’m glad you wrote a short story on top of the script, but it’s not going to help me. But you’re a very good writer.” It is a good exercise. Like the backstory for “GLOW,” that didn’t really help me that much, but I don’t need to tell anybody that.

How have you grown as a collaborator, having coming out of stand-up and podcasting, in which you are pretty much the sole creative force?

MM: I think I’m getting better. I went from something where I write and perform everything to a series where I write, act, produce and be in every scene—that’s rough. But acting is a little more rewarding, where you’re working on scenes and it’s maybe me and one, two or three other people. With “GLOW,” you’re working in segments, and there are a lot of people involved and a lot of waiting around, and it’s hard to figure out how to fill that time. You can stay in character, you can work on your character, you can just sit around, but that’s hard for me because I’m so busy with so many things not to think when I’m sitting around for four hours—I feel like I should be doing something else.

SWORD OF TRUST has such a strange story, and I’ve noticed that a lot of the people who have written about it already are zeroing in on the alt-right, alternate history aspects of it. Do you consider this a film political one some level?

MM: No, I didn’t and I don’t, only to the degree that there is a problem with the nature of truth going on. The idea that people can pick and choose their on truth, and whether it’s true or not isn’t important to a lot of people. But the idea of magical thinking or wanting to believe in something has a long history in this country. It’s more fascinating that people commit to a belief system that directly relates to their anger or feelings over really doing any investigations that might diminish those beliefs. So it’s political in that sense, and there is a red-state trip going on, only in the sense that conspiracy theories have become the bartering tool of political momentum among these type of people. But it’s been on both sides before, and that’s not a false equivalency. The left in the ’60s and ’70s had the full spectrum, but there weren’t engines that would deliver these ideas directly into people’s brains for a specific reason, and they would believe that everything else was some sort of fictionalization or con job.

Having worked with Lynn Shelton in so many different capacities over the years, what do you think makes her stand out as a filmmaker and someone who works well with actors the way she does?

MM: She loves actors. She was an actress; she started there. And then she studied photography and was a film editor, all before she started directing. She has a great aesthetic sense and ability to honor her ability cinematically. But she also has a nuance and an emotional understanding of actors and what they bring to a film. She’s also very engaged in exploring people; she likes people and to engage a lot of empathy, even around people who may be somewhat dubious. Above everything else, she’s a great audience; she likes to laugh and has a great sense of comedy. She’s very into collaboration, which I like. I wasn’t always a collaborator because I didn’t have to be. I was a stand-up; I sit in my garage now and talk to myself or one other person, but I do like the process of collaboration once I get over the insecurity that I’m not getting a word in edgewise.

When she first talked to you about this film for the first time—either in a conversation or if she handed you the script-ment—what do you remember latching onto about this guy initially?

MM: Her and I had been writing a script—and we still are—for almost three years, and we never seem to quite finish it. I don’t like finishing. Having talking to directors and knowing her, but not really knowing how she goes out and shoots a movie—her last film OUTSIDE IN, she went out for a couple of months to make it. I have a hard time knowing what I’m doing the rest of the day, so the idea of making a movie was overwhelming and caused me a great deal of anxiety. But we were in this writing process and it was coming together, but for some reason, I didn’t believe it would ever come to pass or go anywhere, and I think she got—not frustrated—but she wanted to work with me in a film, so she goes “I don’t know when we’re going to get this done, so why don’t I just write a movie for you.” And I’m like, “Alright. Sure, whatever you say, lady.” [laughs]

But she and Mike O’Brien came up with this idea—the went away for a week or two, and she shows up with this pitch that I’m a pawn shop owner. She was inspired by driving past a pawn shop: “Marc belongs in there among the sad objects, the things that people had to part with in desperation.” But it makes sense, I guess. So she hit me with this thing, and I’m like “Okay. I like what you do and I trust you,” but I still didn’t think it was going to happen. It just seemed like this weird thing. “We’re going to shoot it in two weeks.” “Sure. Whatever you say, lady.” And then all the sudden, as we move toward it, my management is like “She’s ready to do this,” and I’m like “Really? We’re going to shoot a movie?” And that’s how it happened, and we did it. We talked about some backstory; I met John Bass and he immediately annoyed me, so that relationship was planted and pretty earnest, and we did it. That’s how it went.

Do you consider these chapters in your career a reinvention or is it more adding to the total person?

MM: A reinvention of me? No. I feel like, hopefully as a person, I’m continuing to engage and pursue my creativity and evolve as a human. I was not necessarily a pillar of good person-ness my whole life. I’ve been somewhat of an asshole in my life, and I’ve been plagued with anxiety and anger. As I open my heart and mind open, I continue to put new stuff into my mind and heart, it comes out in what I’m doing. So I see it more as an ongoing conversation in terms of my stand-up and the podcast, and evolution as a person. It’s part of growth than changing anything. I don’t believe in referring to ourselves as brands; I don’t engage in that kind of conversation.

You’re in this JOKER movie coming out later this year. What are you doing in that, and how did it come about?

MM: Yeah. I think what happened was, I’ve been vocal and critical of the place that superhero movies hold in our culture. And I haven’t seen a lot of them, but not as some sort of defense, but I did see the BATMAN ones. I was never a Marvel guy, but I did read some comics in my life, but I never committed to it as a life. But I was given this opportunity by [director] Todd Phillips; I read for small part in this thing, and he wanted me to do this other part. It was a scene with Robert De Niro and Joaquin Phoenix, and that overtook any sort of criticism. But I also read the script and I know it wasn’t any kind of leotard/cape movie and that it wasn’t a superhero movie as you would expect. It’s a gritty, interesting character study of a mentally ill guy, shot in a very visceral way. So that and having the opportunity to do one scene with the two of them was enough for me to try it.

I know recently you’ve been shooting this David Bowie story [STARDUST]. What is the nature of that? I know that it covers that small period in his life.

MM: 1971, when he came to the states, not really knowing who he is or how the business works, to a degree. The label didn’t know how to selling “The Man Who Sold the World,” and his manager was done with him, and he showed up in the states without the proper paperwork to perform. And I play a Mercury publicist who believed in the guy, and, on a low budget, wanted to do whatever I could do with him that was limited because of his lack of work papers. So it’s me trying to get him into radio stations and private shows, and talking to him about what he wasnts to do with his career, how does he want to present himself. So it’s this odd-couple buddy movie, at least my part of the film is.

Is your character a real guy?

MM: It’s a real guy, but he wasn’t really available to talk to. I don’t think he’s in good health, and there isn’t a lot of footage of him. I don’t know if his family or he would think I did him justice, so I went with the script. It was very scripted, and he director [Gabriel Range] had a short time to do it, so it was a crazy shoot—a lot of 12-hour days and night shoots. I did about two weeks on that too. Johnny Flynn is playing David. It’s a period piece, low-budget movie. Again, I’m really curious to see how it comes together.

I’m curious about the types of roles you might turn down. You don’t have to name the movies, but now that you’re trying to challenge yourself in your acting career, what are you saying no too?

MM: I don’t need to be the punchline. I don’t want to do two-line scenes. I like that SWORD OF TRUST was the dream for me, for an actor who can do what I do, have a nice little bit that has some emotional depth to it and gives me a little bit more screen time, that takes the time to explore something and showcase or challenge me to do something like that, that might not stand out in a bigger movie. It’s the beautiful, funny, small movie that’s getting some attention, which is exciting.

You took classes in college on film criticism.

MM: Yeah, I was a liberal arts major and I minored in film criticism. I studied film from that angle, not ever from filmmaking. I did take a screenwriting course in college at some point, but it was mostly the history of film, the language of film, film crit stuff. I did a concentration on the history of photography in the art history department for a year, and it all came together as a Film Crit minor.

Do you still view films in that more analytical way?

MM: Sometimes. I don’t know what the average person does, and I know there are a lot deeper film nerds than me. I’ve always aspired to be somewhat of an intellectual, but I don’t know that I ever really succeeded. But as I get older, I realize I know what I know and I know what informs me, and I know what I don’t know, and I’ll admit that and I tend to know when I’m wrong fairly quickly. I’m able to trust my intellect for what it is, and it’s unique and somewhat well-sourced. But yeah, I do tend to want to understand movies on that level, but I always feel like I’m falling short intellectually, but that’s just me.

It was great to finally meet you.

MM: Nice to meet you too. Great, man.

SWORD OF TRUST is Now Playing at the Music Box. CLICK HERE for Showtimes & Advance Tickets.

Steve Prokopy is the chief film critic for the Chicago-based arts outlet Third Coast Review (www.ThirdCoastReview.com). For nearly 20 years, he was the Chicago Editor for Ain’t It Cool News, where he contributed film reviews and filmmaker/actor interviews under the name “Capone.”