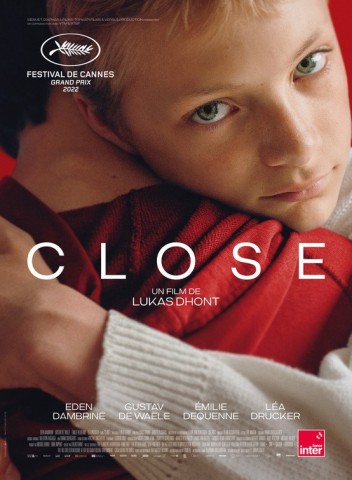

Léo and Rémi are two thirteen-year-old best friends, whose seemingly unbreakable bond is suddenly, tragically torn apart. Winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, Lukas Dhont's second film is an emotionally transformative and unforgettable portrait of the intersection of friendship and love, identity and independence, and heartbreak and healing.

************************************

FARAWAY, SO CLOSE

An Exclusive Music Box Interview with CLOSE writer/director Lukas Dhont.

by Steve Prokopy

Regardless of how the film may have ultimately been received upon release, writer/director Lukas Dhont’s 2018 first feature, Girl, was meant to explore the feminine side of some of the things he experienced as a gay teenager in Belgium. With his second feature Close (also co-written by Angelo Tijssens), Dhont is looking at thing from the masculine part of his personality. Although the sometimes heartbreaking events of Close don’t directly mirror events from his own life, the story of a rift in the friendship between 13-year-old boys, Leo and Remi, caused when classmates accuse them of being gay, is something the filmmaker has experienced at various points in his young life, making this work all the more personal.

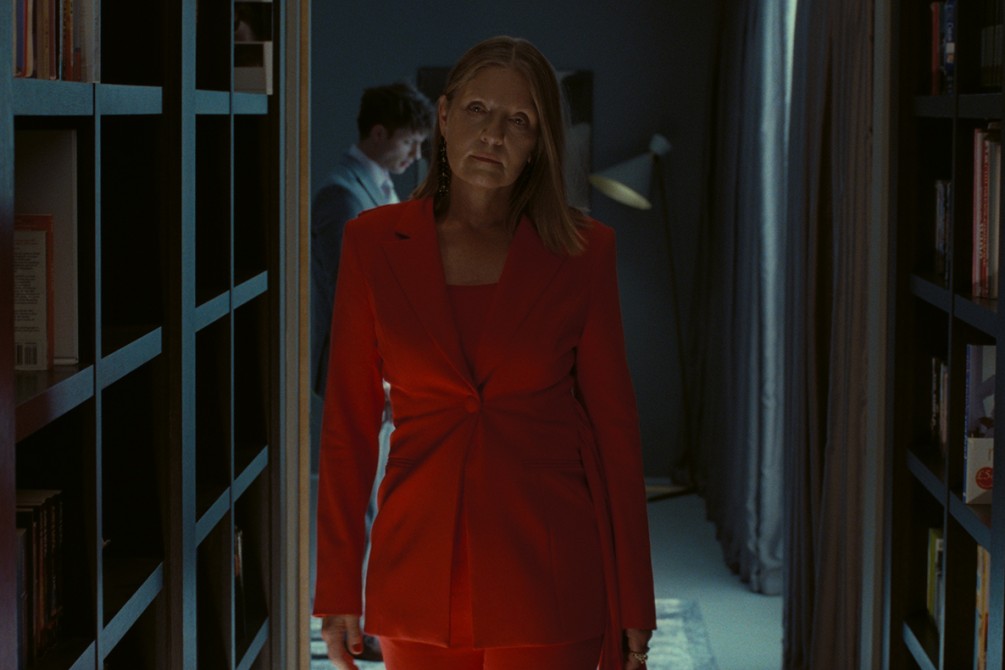

As a result of these accusations, Leo pushes Remi away and soon must deal with the consequences of his actions. Making the matter all the more poignant is that Leo has a close connection to Remi’s mother, who has no idea that the boys’ friendship was in peril. It’s a work about male friendship, responsibility, and the unimaginable weight of guilt on young people. And apparently Academy members were also moved since Close was recently nominated in the Best International Feature category.

I spoke with Dhont while he was in Chicago recently, and he walked us through the genesis of the film and all of the portions of his own life that informed the final screenplay, talked about using two first-time actors in his lead roles, and where he might go thematically with his next film.

Music Box: [Notices that Dhont is wearing a nice suit for his interviews] I didn’t know there was a dress code.

Lukas Dhont: [laughs] It just makes it so much more festive.

MB: It’s nice if people want to take pictures with you.

LD: And I tend to have that, so I better not come dressed… if I could, I’d wear a robe.

MB: I’ve interviewed people in their pajamas.

LD: That is sweet, but because I’m young, I want people to make me more seriously, so I feel if I put in a suit, I have a little bit of class.

MB: With this movie, nobody is going to have trouble taking you seriously, trust me. As I was watching the film, I realized it’s about these two unformed young boys. Are they unformed because of their age or because they’re boys? Are they not quite ready to handle their relationship in other people’s eye because they are young or because they are male?

LD: I don’t consider them immature. These boys are all of us, so when I respond like that, I do think it comes down to them being two young men. We live in this culture that often tends to focus on the brutality between men, the wars being fought between me, rather than men holding on to each other. I feel like we have gotten so numb to these images of violence, and not used to those of tenderness.

When you listen to 13-year-old boys speak about each other and their male friends, they will tell you they’d go crazy without each other. They will tell you they love each other profoundly and openly dare to use the word love, and they maybe are more mature that what comes afterwards. As a society, as we grow up, we learn not to speak that way, because it is often deemed weak or vulnerable or soft to depend that much on someone else, especially if it’s another man. We tell young men at that age that if they want to find intimacy, it will be in sex, not in friendship. Therefore, I have felt that very profoundly at the same age and moment in my life, when I started to fear intimacy and pushed people away, too man people I think. And I was pushed away also.

MB: I was going to ask you, if you were the one who pushed away or got pushed away?

LD: I have been both, yes. Many of us have. There’s this necessity to speak about this construction of vocabulary and that norm we have created for young men. I may be getting into the darkness of it, but the point in time when we stop valuing authentic connections for them is also the time when the suicide rate goes up four times.

MB: It’s a learned behavior, to closeness between two kids this age makes some people feel uncomfortable. Have you ever thought about what about that makes people uneasy?

LD: Because we have created a different language for men. Men are meant to be the lone cowboy, the one who protects and is independent, who competes and is strong. We often think in those terms. And we live in a society where everything that is hard and brutal is on top and smothers the soft. I can see that clearly when I look at my father or grandfather or even myself, and what happens is that young boys are so preoccupied with what they’re not—feminine, gay—they forget who they are. If you spending so much time thinking about who you’re not, you’re not focusing on who you are. So let’s start focusing on that.

MB: In addition to drawing from your own experience, did people also tell you stories that resonating with you, or did you read stories? Where else did you pull from?

LD: There was a friend of mine who recommended a book to me called Deep Secrets [Boys’ Friendships and the Crisis of Connection], which has studies done by New York psychologist Niobe Way. She really gave me the key for what eventually became the film because she followed the lives of 150 boys here in America, and she asked them at the age of 13 to talk about their male friendships, and they talk about it in a very loving, tender way. And then she asked those questions again at 16, 17, 18, and what you uncover is that, as they grow older, they don’t speak in that way anymore. Having that research with all of these boys made me realize that it is something that we all share. Then I connected my own experience to it, and bit by bi, this film came to life.

MB: Was the suicidal element of Close always a part of the film? I think you could have told a very compelling story about two kids drifting apart, and that would have hit pretty hard. But you go in a different direction.

MB: I could have done it differently, but then it wouldn’t have touched on all the blistering topics that it touches on. It wouldn’t have touched on mental health, or on this very taboo subject of suicide. To quote Nan Goldin: “We have to de-stigmatize talking about that.” We have been filming wars between people for such a long time and have forgotten to focus on the wars that it creates, on the inside. It’s also a film about grief, about loss—it’s grief filmed through a child’s gaze, and this gaze comes with guilt.

MB: I might say guilt trumps all else for this boy. He might never fully recover from it.

LD: I don’t know about that. When we lose someone in that way, there is the question of responsibility, whether he is responsible or not. It’s a much more complex situation than A + B = C, and there is this shared mother with the mother, where we have two characters who clearly feel guilty and are able to exteriorize it—some of us are never able to do that. When we are kids, we feel responsibility for the first time, all of us; guilt for the first time. Many of us carry it with us, carry it on our back, in our bodies, and we’re never really able to exteriorize it. There is an importance in that, in being able to speak of the things that shut us off from the world, that are our invisible armor.

MB: I don’t know anyone who has seen this movie that hasn’t told me they break down crying at some point. Was it as emotional for us making it as it is for us watching it?

LD: Oh yeah. For me, it’s been a transformative journey because it’s about speaking about a wound that I have carried around since childhood. What is so emotional in it is that it connects a wound in the audience that has been kept inside and not been revisited. When we’re young, we go through things for the first time and we continue. It’s this wound that stays there, the one we haven’t cried for, the one we haven’t confronted or looked in the eyes; it’s for regrets, we have all regretted something, and some of us stronger than others. Regret is a strong, powerful feeling, and the film touches on that. I’m not Greek, I’m Belgium, but do believe strongly in what the Greek call catharsis. When we confront a collective wound, there’s a catharsis that can come out of it. The film is about bruising and healing, and I’m one of those optimists that believes we can heal from trauma.

MB: These kids are, in fact, very mature, and the relationships the boys have with the other’s parents are really impressive, and that scene near the end with Leo and Remi’s mother works unless we know how closely connected they are. And you have these first-time actors working with professionals, so were there any surprises about doing that, things you learned from collaborating with first-time actors that maybe you weren’t expecting?

LD: Yeah, we all know that it’s such a strange, different relationship with parents of your friends. It’s not your parents, but it’s adults, and somehow there’s the possibility for friendship at that age with the parents of your friends. There’s a different type of connection than with your own parents, or at least I had that. I wanted to give that idea space in the film. The character of Sophie, played by Émilie Dequenne, who is one of our great Belgian actresses, and the character of Leo have very similar parts because they both have this armor on, one literally and one more invisible. When we lose someone, so often we feel guilt. What I love is this combination of adult actors with those who have never acted before; I think there’s a kind of magic that happens in the confrontation between them. One who relies on all this technique and one who relies on the heart, the emotion, and when they come together, it can be incredibly powerful.

I worked with the young cast for six months, because I want to build family, intimacy, all these things with them before we arrive on set and before we create what we’re going to create. During that rehearsal, I’ll bring in the adult actor for a little bit, so that they can get used to them and get this bond created, and Léa Drucker, who plays Leo’s mother, reminded me of some direction I gave her on the very first day when she asked me how I envision this collaboration. She said, “I’ll never forget because it was so primal what you said, but so true: ‘The thing I need from you is for you to love Eden [who plays her son Leo].’” It seems basic but it’s not. When you have that connection, I strongly believe you can sense it, and it’s a space where you can start creating.

I went to a film school that combined documentary and fiction, and I have very naturalistic approach to working with the actors and an impressionistic approach when it comes to color, light, and movement. But in my work with the actors, I try to incorporate all of these things I learned from documentary. When I work with them, I try to find authenticity in the work and the freedom for them to move.

MB: Both of your first two film were very personal to you in different ways. Do you ever see a time that you might work on something that you didn’t have a hand in creating from the ground up?

LD: I can, but it still need to be personal. How would I give all of these interviews or talk with so much passion if it weren’t personal. Personal doesn’t mean it’s not, at the same time, universal. It needs to start from the space where I feel that it’s necessary for me to talk about it. Can that happen through the writing of someone else? I do believe so, but I need to find what it is in that writing that feels urgent for me.

MB: Do you have a sense what you’ll be doing next?

LD: Slowly but surely [laughs[. I’m getting there.

MB: Best of luck with this. Thank you so much for talking.

LD: Thank you. Great meeting you.

Steve Prokopy is the chief film critic for the Chicago-based arts outlet Third Coast Review (www.ThirdCoastReview.com), a co-host of the Movie Madness podcast, and the Public Relations Manager for the Music Box Theatre. For nearly 20 years, he was the Chicago Editor for Ain’t It Cool News, where he contributed film reviews and filmmaker & actor interviews under the pseudonym “Capone.”

Recommended Films